A brief summary based on two datasets

Ashok Nag

Adam Smith began his magnum opus “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations”, with the following line:The annual labour of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniences of life which it annually consumes. (Smith- 1776; EBC edition 2001: Book 1 page 12)

For a given amount of labour, according to Smith, the wealth of a nation will on the productivity of that labour. While there is no inherently intrinsic level of productivity of a human being, it can be worked upon and enhanced by appropriate organizational structure, technological initiatives and incentives. According to Smith, the “greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgement with which it is anywhere directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labour.”(op.cit. page 17) It is not that the nature’s bounty – land, water, and environment- does not give a head start to a particular nation, but it would not make a nation wealthier if the “skill, dexterity, and judgment” and “division of labour” are not well developed and do not become an integral part of the production system.

Notwithstanding Smith’s identification of “labour” as the source of all wealth, he was pragmatic enough to understand that a market economy is not designed to bring the maximum benefit to providers of labour that creates wealth. In fact, he was aware that a market economy, per se, has no institutional mechanism for reduction of inequality in distribution of a nation’s wealth, and, therefore, it cannot bring about more equality in distribution of initial endowment of wealth that provides enormous advantage only to a small minority of people. His main concern was the growth of an economy- a growth that critically depends on the increase in productivity of labour. He had no illusion about the antagonistic nature of relation between wage earners and profit earners. Smith, an astute observer of social power structure and author of Theory of Moral Sentiments, understood the real mandate of any civil government:

Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor, or of those who have property against those who have none at all (Smith: op.cit. Book 5 page 953)

This article shows that, even after 250 years of Smith’s assertion that labour is the ultimate source of wealth, the share of a nation’s wealth remains concentered in the hands of rich. The remit of all civil governments and international organizations remain the same- to enforce and maintain the inequality in wealth and power within and without a nation.

Definition of wealth

Etymologically, the English word “wealth” traces its ancestry to the old English “weal” and before that to “wel”. Both these words referred to a general state of “wellbeing “. The circularity in this definition notwithstanding, for people at large, possession of material “wealth” is both necessary and sufficient condition for a person’s wellbeing. In order to measure wealth in possession of an individual, family or a community, we need to identify valorized components of wealth. Irving Fisher, in his book, “The nature of capital and income” , defined and elucidated the term “wealth” in a market economy in the following manner.

The term ” wealth” is used in this book to signify material objects owned by human beings. According to this definition, an object, to be wealth, must conform to only two conditions: it must be material, and it must be owned. To these, some writers add a third condition, namely, that it must be useful. But while utility is undoubtedly an essential attribute of wealth, it is not a distinctive one, being implied in the attribute of appropriation; hence it is redundant in a definition. (Fisher 1906,page 3).

For Fisher ownership of material goods is a necessary qualification of a material object to be considered as a part of a legal entity’s wealth. He clarified this with following examples:

Rain, wind, clouds, the Gulf Stream, the heavenly bodies — especially the sun, from which we derive most of our light, heat, and energy — are all useful, but are not appropriated, and so are not wealth as commonly understood. (op.cit page 3)

More than one hundred years have passed since Fisher gave his definition of wealth. Today, even clean air is not only a desirable but a precious material object too. According to UN Environmental Program, air pollution is the greatest environmental threat to public health globally and accounts for more than 8 million premature deaths every year. A number of recent empirical studies have shown that polluted air has a negative impact on labour productivity and thereby on human capital component of a nation’s wealth (see Chen and Zhang 2021). Thus, measured degradation in the quality of environment needs to be considered as a liability that must be deducted from the value of asset. It also highlights the complexity and contradictions in the concept of ownership , especially when accounting for environmental impact. For example, access to natural resources like living and non-living useful objects in sea has been demarcated with a national boundary based on international agreement and are always prone to conflicts between nations. Similarly, the question of whether possession equates to ownership is a complex legal issue. When Smith or even Fisher wrote about wealth, they did not have to deal with the issue of ‘knowledge as a source of wealth”. For them “skill, dexterity” of individual workers, combined with “judgement” of entrepreneurs created wealth.

It is quite evident that the concept of wealth is as fuzzy as its equivalent concept of wellbeing. The definitional issues of ‘wealth” is beyond the scope of this article, although measurement of “wealth” of a nation would depend on the demarcation of the underlying definitional boundary. Since there is no globally accepted definition of wealth of a nation, for this study, we have used two well recognized datasets on national wealth- one by the World bank that provides wealth data from 1995 to 2018 and another one by the Credit Suisse (now UBS) that provides data on household wealth since 2000. Credit Suisse (now UBS) is a globally active financial institution having a very large wealth management practice. Although we take a quick over view of wealth measured across nations, our focus is on three largest nations- China, India, and USA. (Reference part of this article gives the details of all reports of these two agencies)

| Box 1 Data Quality The two datasets that we have used for our evaluation of distribution of wealth, across the nations and within a nation, are subject to many qualifications. A brief discussion of the most important ones follows. The World Bank calculates the present value of future flows of produced outputs generated by land, labour and capital – that is a country’s GDP- by using a time-independent discount factor uniformly for all nations. This approach may introduce inaccuracies since each country’s economic conditions vary from country to country. On the other hand, the Credit Suisse /UBS evaluates household wealth, which includes “financial assets and real assets (principally housing)” using market value, wherever available, (see Notes on concepts and methods page 19 of 2023 UBS report). However, due to the volatility of financial markets, price movements in one country may not align with those in others, leading to inconsistent valuations across countries. At the country level, domestic currency is typically used for valuation of assets, but for international comparisons, a conversion to a common currency is required. The World Bank does this by using market exchange rates in constant 2018 US dollars. The Bank also looked at how using Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) based exchange rates affects this measure. When using PPP, the share of global wealth for low-income and lower-middle income countries rises from 7.3% to 15.8%. The Credit Suisse/UBS used end period market exchange rate to convert local currency estimates into US dollar-based estimates. The price volatility, degree of market dominance by a few large corporates etc. are key features that vary from market to market. Such variations is far from negligible and in the absence of any normalization of data across markets, its impact on the wealth distribution data remains unaddressed. Apart from measurement issues, wealth data even at national level is fraught with a number of conceptual issues, particularly concerning definitional boundary of Natural Capital and Human Capital. For example, the assessment of a country’s natural wealth depends on available knowledge about resources located within its recognized borders. These borders are determined according to international agreements, and any limitations in resource knowledge can affect wealth calculation. In spite of having many data such quality issues, the two data sets used in this article are the only ones that provide complete coverage of wealth of nations over a reasonably long time. |

Estimation methodology of National Wealth by the World Bank:

Components of wealth:

Where is the wealth of nations? (World Bank 2006) was the first attempt by the Bank to provide “comprehensive snapshot of wealth for 120 countries at the turn of the millennium”. Since 2006, the Bank is publishing a yearly report titled The Changing Wealth of Nations: Managing Assets for the Future (CWON). This article uses data published in the 2021 report, the latest available.

To measure a nation’s wealth, the World Bank relies on two closely related international standards for valuing economic activity within national borders. The first standard is the System of National Accounts (SNA), which focuses on national income measurement. The United Nations Statistical Commission (UNSC) released the first version of SNA in 1953, with the latest update in 2008. The SNA bases its accounts on transactional data related to production, consumption, and the accumulation of assets. The institutional units participating in these exchanges within a market economy generate this data.

The System of National Accounts (SNA) defines an asset as “a store of value.” Any rent or profit generated from this asset must accrue to the “economic owner” in the future. Following the principles of Irving Fisher, the SNA does not consider any store of value without identifiable economic ownership as an asset. (page 39 para 3.5 SNA 2008). Following Irving Fisher, SNA also does not recognize any store of value that has no identifiable economic ownership, as an asset.

The second standard, introduced in 2012 and used by the Bank, is the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA), which is the accepted international standard for environmental-economic accounting. The SEEA framework acknowledges the inherent link of every production system to its surrounding environment, and its significant impact on all production activities by human beings. These environmental impacts include the depletion of natural, non-produced resources, such as forests, minerals, and air, as well as a reduction in the quality of environment, which ultimately undermines the production process itself. The concept of sustainability in growth stems from the recognition that the environment may eventually be unable to sustain such production levels. In terms of accounting principles, conventions, and table structures, the SEEA aligns with the SNA.

The core premise of the World Bank’s methodology is that a nation’s wealth consists of three major types of assets or capital: produced assets, natural capital, and human resources. Human resources include raw labor, human capital, and the intangible yet essential element known as social capital (World Bank 1997, Page 19). An outline of the definitions and boundaries for each of these components follows.

Produced Assets:

SNA 1993 defined “produced assets” as “non-financial assets that have come into existence as outputs from processes that fall within the production boundary of the SNA; produced assets consist of fixed assets, inventories and valuables.” Thus, human capital, and natural resources without any identified owner are excluded (Paragraphs 10.7 and 13.14, see also SNA 2008 page 48 para 3.49)

Three types of produced non-financial assets are:

- Fixed assets,

- Inventories, and

- Valuables, which include items like precious metals, antiques, and art objects.

Non-produced assets comprises of three sub-groups:

- Natural resources,

- Contracts, leases, and licenses, and

- Goodwill and marketing assets.

Natural Capital

Natural capital comprises of three principal categories: natural resource stocks, land and ecosystems. Natural resources are non-renewable resources like oil, natural gas, coal and mineral resources. Land includes cropland, pastureland, and forested areas. Ecosystem assets are those assets, which provide ecosystem services that are essential for sustainability of any human society. In environmental accounting, ecosystem incorporates both living organizations and the physical environment encompassing them in a specific area comprising landscape as well as seascape (see Estelle Dominati et al 2010, United Nations 2003). The CWON 2011 report provides further details about these Ecosystem Services and measurability of them. (CWON 21 page 22)

Human Capital

The three attributes of labour, namely “skill, dexterity, and judgement” are the main drivers of labour productivity. The income that a laborer earns in her lifetime can be considered as “flow of rents (or economic profits) in the future.”(page 3 CWON 2011). Accordingly, the Bank measures Human Capital as the present value of all future labour income (2021 CWON report page 144).

| Box 2 Genuine Savings Wealth, in the form of produced assets, increases through savings and investment. Net national savings are calculated by subtracting the consumption of fixed capital from the gross national savings, as per the System of National Accounts (SNA). Consumption of fixed capital reflects the depreciation of productive capacity during the estimation period. This measure of net national savings, however, does not account for the sustainability of economic growth, as it overlooks changes in natural resource bases and environmental quality besides produced assets (as highlighted in “Expanding the Measure of Wealth,” page 8). Consequently, the value depletion of natural resources like energy, metals, minerals, and net forest stocks is estimated and subtracted from the net national savings. Since education enhances human capital, current expenditures on education are added to the net national savings. This adjusted figure is known as genuine savings. Many natural resource-dependent countries exhibit low or negative genuine savings, indicating long-term sustainability issues. |

Measurement of wealth

From the perspective of sustainability of current economic growth, measurement of wealth at a time t needs to be the sum of all future consumption, appropriately discounted on future consumption path. Symbolically, this has been written as: where Wt is the present value of future flows of income in the year t, C(S) the is the consumption in a future year s , and r is the social return to investment or the discount factor for future benefits. The Bank has taken 24 years as the time horizon for its wealth computation. As regards the social discount factor, 4 per cent has been used. The Bank has not provided any counterfactual study with regard to these assumptions. However, comparison of change in wealth across nations may not suffer from gross errors, provided that the degree of errors is bounded across nations. Similarly, a nation’s income as measured by GDP represents the cash flows generated from the produced wealth of the nation. Essentially, estimating a nation’s produced wealth becomes straightforward with an assumed income (i.e. GDP) growth rate and a given discount factor. The World Bank data is available from 1995 to 2018. For a given year, the total wealth is the sum of the following components:

Total wealth = renewable natural capital + nonrenewable natural capital+ produced capital + human capital + net foreign assets. Data given in 2021 CWON is in constant USD 2018, at market exchange rate. All data has been sourced from https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/wealth-accounting

Estimation methodology of Household Wealth by Credit Suisse/ UBS

Credit Suisse, a Switzerland-based global investment bank, was established in 1856. Since 2010, the bank has been publishing the Global Wealth Report (GWT), which provides profiles of household assets across various nations. An accompanying publication, titled the Global Wealth Databook, offers detailed data that underpins the main report. In March 2013, Credit Suisse was acquired by another Swiss bank, UBS, in an all-stock deal orchestrated by a joint effort of the Swiss government and the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority, to prevent the potential fallout from a Credit Suisse bankruptcy. UBS has continued publishing the Global Wealth Report since 2023. The latest report was published in July 2024.

In contrast to the World Bank’s approach, GWT estimates wealth solely at the household level. At this level, net worth, or ‘wealth,’ is defined as the market value of financial and non-financial assets owned by a household, minus any debt. Real assets consist primarily of housing properties owned by households. This approach does not include human capital, natural capital, or other elements considered in the World Bank’s method for measuring national wealth. Additionally, government or community-owned assets are excluded (see Davies et al). To ensure consistency in measuring wealth across nations, all asset valuations are converted to US dollars using the end-period exchange rate. For assessing the wealth of individuals at the top end of the distribution in each country, the data is adjusted using wealth estimates given by in the Forbes list of billionaires.

Wealth of Nations – World Bank estimates

Between 1995 and 2018, global wealth increased from 603.5 trillion USD to 1152.5 trillion USD- indicating a compounded growth rate of 3.4 %. Only in two years- 2006 and 2007, the growth rates were more than 4%. The composition of wealth remained more or less the same during this period. During the same period, the Global GDP at constant 2015USD increased by a compound growth rate of 3.1%. The average shares of three major components, Produced Capital, Natural Capital and the Human Capital – remained at around 51.5%, 6.7% and, 62% respectively (see annexure table A2.1 and A2.2).

The global wealth is concentrated in two high-income group of countries, namely OECD and non-OECD countries. Non-OECD high-income countries, such as the UAE and Bahrain, have a very low population share, only 1% in 2018. As a sub-group, their share in total wealth remained between 2% to 3%. Although high-income OECD countries continue to hold the largest share of the world’s total wealth, their share declined from 74.3% to 58.3% between 1995 and 2018. During the same period, their corresponding population share also declined modestly, from 17.6% to 15%. Lower middle-income countries, including India, accounted for the highest share of the world’s population in 2018 (39.7%) but held a very modest share of the world’s total wealth (5.7%). Human capital was the largest source of wealth for most countries, except for high-income non-OECD and low-income countries. The share of natural capital in total wealth was the lowest for high-income OECD countries, at a mere 2.1%. This suggests that the bounty of nature is neither necessary nor sufficient for the generation of wealth (see Table A2.3). Data on country wise shares in wealth and population shows that the top ten countries in terms of their wealth in 2018 have hardly changed between 1995 and 2018. The entry of China in this club of rich countries has compensated for the decline in the share of High-income OECD countries. These top ten countries accounted for around 72% of total global wealth and around 55 percent of the world’s population. The most important takeaway from these estimates of national wealth is the phenomenal rise of China. In 1995, China’s wealth was only 22 percent of USA’s wealth and by 2018, it has reached to 85%. During this period, the ratio of China’s population to that of USA remained almost the same- 4.5 in 1995 to 4.3 in 2018 (see Table A2.6). The shares of China, India, and USA in the total wealth of the world, given below, shows how China has leapfrogged to become the wealthiest country of the world.

Table 1: Wealth Share versus Population Share of countries

| Year 2000 | Year 2010 | Year 2018 | ||||

| National Wealth Band | Share in World Population | Share in Wealth of the World | Share in World Population | Share in Wealth of the World | Share in World Population | Share in Wealth of the World |

| less than 1 trillion | 13.5% | 2.7% | 13.8% | 2.6% | 12.4% | 2.3% |

| 1-5 trillion | 21.0% | 10.9% | 20.9% | 9.9% | 18.4% | 6.9% |

| 5-10 trillion | 7.1% | 7.2% | 1.8% | 4.2% | 7.4% | 0.0% |

| 10 – 50 trillion | 29.7% | 29.6% | 36.5% | 33.8% | 35.0% | 27.7% |

| More than 50 trillion | 28.8% | 49.6% | 27.0% | 49.5% | 26.8% | 56.8% |

China’s increasing footprint in the world economy is not only consistent with its growth in its national wealth but also with the growing prosperity of its average citizen. Thus, the per capita GDP growth rate of China during the period 1995 -2023 remained well above the corresponding growth rates of India as well as USA. The data given below corroborates this.

Table 3: Growth in per capita GDP of China/India/US

| Per capita GDP- Compound Growth Rate | |||

| China | India | USA | |

| 1960-1970 | 2.4% | 3.0% | 5.7% |

| 1970-1980 | 5.6% | 9.1% | 9.2% |

| 1980-1990 | 5.0% | 3.3% | 6.6% |

| 1990-2000 | 11.7% | 1.8% | 4.3% |

| 2000-2010 | 16.8% | 11.8% | 3.0% |

| 2010-2020 | 8.6% | 3.6% | 2.8% |

| 2020-2023 | 6.6% | 9.1% | 8.3% |

| 2023 GDP as ratio of US GDP | 0.15 | 0.03 | 1 |

Wealth of Nations – Credit Suisse/ UBS estimates

The 2024 Global Wealth report estimates 4.2 % increase in global wealth ( in USD) in 2023 as compared to a decline of (-)3% in 2022. The report has highlighted that in the last 15 years of publication of this report only 3 times there has been a decline in the estimated global wealth in USD term- “during the financial crisis of 2008, in 2015 and once again in 2022, when both equities and bonds dropped across all major markets” ( page 5).

Table 4 Distribution of Global Household Wealth- 2022

| Wealth range ( in thousand USD) | No of adults (million) | No of adults (%) | Total wealth in Trillion) | Wealth percentage |

| less than 10K | 2818 | 52.5 | 5.3 | 1.2 |

| 10K-100K | 1844 | 34.4 | 61.9 | 13.6 |

| 100K-1million | 642 | 12.0 | 178.9 | 39.4 |

| >1 million USD | 59.4 | 1.1 | 208.3 | 45.8 |

The wealth distribution for China, India, and USA, countries in focus of this article shows that India stands apart from the other two most populous countries.

Table 5: Wealth Distribution of Adults for the China, India , and USA -2022

| Wealth range ( in thousand USD)- | Distribution of no of adults (%) | ||

| China | India | USA | |

| less than 10K | 19.3% | 73.8% | 17.5% |

| 10K-100K | 65.6% | 24.0% | 30.3% |

| 100K-1million | 14.5% | 2.1% | 43.2% |

| >1 million USD | 0.6% | 0.1% | 9.0% |

| Gini Coefficient of wealth distribution | 70.9% | 82.5% | 83.0% |

Finally, we find that acute wealth-deprivation of 90% of Indian people has made no adverse impact on the rising wealth of 1% of people at the top of the pyramid of wealth. In fact, between 2002 and 2018 the share of the top 1 % of India’s wealth owners have increased from 15.7% to 18.3%. At the same time, the share of the bottom 90% of wealth owners hovered around 47%. For both China and USA, there has been similar increase in inequality in distribution of wealth.(see the table A2.13 ).

In a market economy, financial wealth is the dominant form of total wealth of households. In China, the share of financial wealth has increased from 36.4% to 45.4 % between 2000 and 2022. During the same period, the share of the financial wealth in the gross wealth held by Indian households decreased from 24.1% to 21.0%. The share of financial wealth in the gross wealth of households in USA hovered around 68% during the same period.(see Table A2.14)

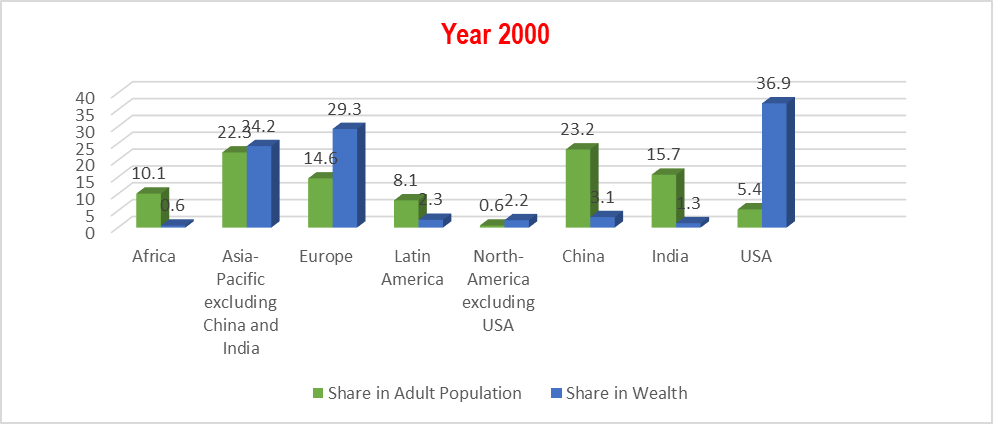

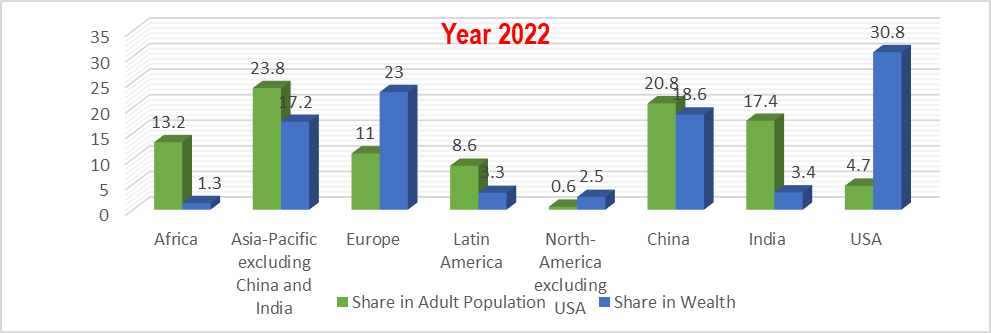

The regional distribution of household wealth shows that world continues to remain highly unequal. In the year 2000, Africa, Latin America and India together accounted for 33.9% of the adult population of the world and only 4.2% of household wealth of the world. In the same year, the corresponding shares of Europe and USA together were 20% and 66.2 percent. By 2022, the share in total adult population did not change much for the first group, but its share in the wealth almost doubled from 4.2% to 8%. For the second group, both the shares declined to 15.7% and 53.8% respectively (see the Annexure Chart 1). The most remarkable fact about the changing distribution of the world’s wealth is the phenomenal rise of China’s wealth share. It increased from 3.6% in 2000 to 18.6% in 2022- a fivefold increase. During the same period, China’s share in adult population decreased from 23.2% to 20.8%.

One noteworthy feature of growth of household wealth in this millennium is the drastic fall in growth rate between two decades for some selected markets. The Annexure table A2.10 shows that annual compounded growth rates for household wealth has more than halved for many important countries between 2000-10 and 2010-23. For example, the household wealth growth rate (compounded annually) of Russia declined from 20% in the first decade to only 4% in the next period of 13 years. The corresponding figures for China and India were (19,8) and (14,7) respectively. The comparable growth rate for USA was 4 and 6 respectively.

Billionaires of the world with special reference to China. India and USA

Forbes, an USA based business magazine, publishes every year a global list of US dollar billionaires. The magazine published its first list in 1987. Between 1987 and 2024, the number of billionaires in the world have increased from 470 to 2781, with their net worth having increased from $898 billion to $14.9 trillion. A comparison with total household net wealth published by UBS shows that the share of billionaires in total household wealth increased from 1.42% in 2005 to 2.8% by 2022. (See the chart).

In India, 166 billionaires own 4.9% of total household wealth of India in the year 2022, while the corresponding numbers for China and USA are 2.3% and 3.4% respectively.

UBS in collaboration with PWC has also been publishing a report on billionaires of the world since 2015. covering mostly 43 markets in the Americas, Europe, the-Middle East and Africa (EMEA) and Asia-Pacific. In 2023, UBS/PWC study covered 2544 billionaires as against 2376 in the previous year. The report provides an interesting insight into the persistence of wealth in an already wealthy family. During the study year 2023, 53 multi-generation billionaire inherited USD 150.8 Billion, while 84 new first generation billionaires were worth of USD 143.7 Billion. ( UBS 2023, page 24 Section 2 )

The main conclusion that we can safely draw from the data assembled in this article is that the distance between elites and the poor in terms of opportunity dominance within a given society of Homo sapiens has not changed noticeably, from the times when our ancestors started accumulating wealth. Annexure 3 provides a brief discussion of inequality prevailing in such ancient human societies that existed between 11000 to 2000 years ago.

Annexure 1 Charts

Chart1: Share of Regions and 3 most Populous countries in the world’s adult population and wealth (in %)

Source : Global Wealth Databook 2023 UBS

Chart 2: Number of Billionaires of the World- and their share in the World’s Wealth

Source : https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/guillemservera/forbes-billionaires-1997-2023

Annexure 2: Tables

Based on the World Bank Data

Data source for all World Bank Data: The Changing Wealth of Nations 2021: Managing Assets for the Future and https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/wealth-accounting

Table A2.1: Income group wise share in global wealth and population

| Year | 1995 | 2010 | 2018 | |||

| Income Group | Share in total wealth | Share in population | Share in total wealth | Share in population | Share in total wealth | Share in population |

| High income: non-OECD | 2.18% | 0.77% | 2.82% | 0.96% | 2.64% | 1.05% |

| High income: OECD | 74.32% | 17.64% | 64.02% | 15.88% | 58.26% | 15.01% |

| Low income | 0.49% | 5.78% | 0.53% | 7.24% | 0.59% | 8.26% |

| Lower middle income | 4.98% | 36.29% | 6.11% | 38.77% | 6.73% | 39.72% |

| Upper middle income | 18.04% | 39.52% | 26.52% | 37.14% | 31.78% | 35.96% |

Table A2.2 : Share of various wealth types for different income groups– Year 2000

| Income Group | Share of Produced Capital | Share of Natural Capital | Share of Human Capital | Share of Net Foreign Assets |

| High income: non-OECD | 18% | 34% | 38% | 10% |

| High income: OECD | 34% | 2% | 65% | 0% |

| Upper middle income | 27% | 13% | 60% | -1% |

| Lower middle income | 27% | 19% | 58% | -3% |

| Low income | 26% | 39% | 39% | -3% |

corresponding income group.

Table A2.3: Share of various wealth types for different income groups– Year 2010

| Income Group | Share of Produced Capital | Share of Natural Capital | Share of Human Capital | Share of Net Foreign Assets |

| High income: non-OECD | 17.7% | 42.2% | 31.9% | 8.2% |

| High income: OECD | 35.9% | 2.8% | 62.0% | -0.6% |

| Upper middle income | 23.6% | 13.9% | 62.4% | 0.0% |

| Lower middle income | 24.5% | 18.3% | 59.3% | -2.1% |

| Low income | 25.8% | 34.2% | 41.7% | -1.8% |

Table A2.4: Share of various wealth types for different income groups– Year 2018

| Income Group | Share of Produced Capital | Share of Natural Capital | Share of Human Capital | Share of Net Foreign Assets |

| High income: non-OECD | 23.2% | 30.8% | 33.6% | 12.4% |

| High income: OECD | 35.0% | 2.1% | 63.8% | -0.8% |

| Upper middle income | 25.8% | 7.9% | 66.2% | 0.1% |

| Lower middle income | 27.2% | 13.5% | 62.1% | -2.8% |

| Low income | 27.7% | 25.6% | 50.0% | -3.3% |

Table A2.5: Average growth rate of total wealth for five-year period by regions

| Year | East Asia & Pacific | Europe & Central Asia | Latin America & Caribbean | Middle East & North Africa | North America | South Asia | Sub-Saharan Africa | World |

| 1995-2000 | 3.91 | 1.75 | 2.40 | 2.50 | 3.75 | 4.60 | 0.49 | 3.01 |

| 2001-2005 | 4.08 | 1.63 | 2.55 | 5.22 | 1.71 | 5.22 | 3.27 | 2.51 |

| 2006-2010 | 5.73 | 1.73 | 3.87 | 6.57 | 1.05 | 6.14 | 6.94 | 3.05 |

| 2011-2015 | 5.34 | 1.29 | 3.47 | 3.75 | 1.78 | 5.46 | 4.26 | 3.04 |

| 2016-2018 | 4.31 | 1.76 | 1.31 | -2.31 | 1.71 | 5.90 | 1.85 | 2.54 |

Table A2.6 Share in total global wealth and population for top ten countries in terms of wealth in 2018.

| Country | 1995 | 2000 | 2010 | 2018 | ||||

| Share in Wealth | Share in Population | Share in Wealth | Share in Population | Share in Wealth | Share in Population | Share in Wealth | Share in Population | |

| United States | 30.10% | 4.89% | 31.41% | 4.84% | 27.05% | 4.69% | 24.73% | 4.74% |

| China | 6.69% | 22.11% | 8.49% | 21.48% | 15.20% | 20.22% | 21.07% | 20.75% |

| Japan | 10.52% | 2.28% | 9.68% | 2.16% | 7.25% | 1.92% | 6.14% | 2.02% |

| Germany | 6.45% | 1.49% | 5.86% | 1.40% | 5.09% | 1.21% | 4.84% | 1.30% |

| France | 4.44% | 1.09% | 4.25% | 1.04% | 3.66% | 0.98% | 3.29% | 1.01% |

| United Kingdom | 3.63% | 1.06% | 3.72% | 1.00% | 3.17% | 0.95% | 2.85% | 0.98% |

| India | 1.50% | 17.84% | 1.66% | 18.26% | 2.26% | 18.81% | 2.83% | 18.52% |

| Canada | 2.95% | 0.54% | 2.85% | 0.53% | 2.79% | 0.52% | 2.64% | 0.52% |

| Russian Federation | 2.99% | 2.69% | 2.56% | 2.48% | 2.61% | 2.15% | 2.17% | 2.30% |

| Brazil | 2.53% | 2.99% | 2.35% | 3.01% | 2.45% | 2.97% | 2.13% | 2.98% |

| Total | 71.80% | 56.98% | 72.83% | 56.21% | 71.54% | 54.42% | 72.69% | 55.11% |

Table A2.7: Comparison of three selected countries in terms of per-capita wealth

| Country Name | Per capita 2000 | Rank | Ratio to Median | 2010 per capita | Rank | Ratio to Median | 2018 per capita | Rank | Ratio to Median |

| United States | 779093 | 6 | 18.4 | 804679.9 | 5 | 13.3 | 872400 | 6 | 13.7 |

| China | 47046 | 72 | 1.1 | 104563.4 | 52 | 1.7 | 174365 | 41 | 2.7 |

| India | 10972 | 121 | 0.3 | 16875.8 | 118 | 0.3 | 24102 | 110 | 0.4 |

Table A2.8: Share in Total Wealth of the World by three largest countries in terms of population

| Country | 1995 | 2000 | 2010 | 2018 |

| China | 6.7% | 8.5% | 15.2% | 21.1% |

| India | 1.5% | 1.7% | 2.3% | 2.8% |

| USA | 30.1% | 31.4% | 27.0% | 24.7% |

| Total | 38.3% | 41.6% | 44.5% | 48.6% |

A2.9: Average growth rate of total wealth for 5 year period by regions

| Year | East Asia & Pacific | Europe & Central Asia | Latin America & Caribbean | Middle East & North Africa | North America | South Asia | Sub-Saharan Africa | World |

| 1995-2000 | 3.91 | 1.75 | 2.40 | 2.50 | 3.75 | 4.60 | 0.49 | 3.01 |

| 2001-2005 | 4.08 | 1.63 | 2.55 | 5.22 | 1.71 | 5.22 | 3.27 | 2.51 |

| 2006-2010 | 5.73 | 1.73 | 3.87 | 6.57 | 1.05 | 6.14 | 6.94 | 3.05 |

| 2011-2015 | 5.34 | 1.29 | 3.47 | 3.75 | 1.78 | 5.46 | 4.26 | 3.04 |

| 2016-2018 | 4.31 | 1.76 | 1.31 | -2.31 | 1.71 | 5.90 | 1.85 | 2.54 |

Credit Suisse / UBS Data

Table A2.10 Comparison of wealth growth rates over time

| Country | 2000-10 | 2010-23 |

| Russian Federation | 20 | 4 |

| Mainland China | 19 | 8 |

| UAE | 16 | 4 |

| Brazil | 15 | 3 |

| India | 14 | 7 |

| Indonesia | 13 | 6 |

| South Africa | 13 | 2 |

| France | 10 | 2 |

| Italy | 7 | minus 0 |

| Germany | 6 | 3 |

| Japan | 6 | minus 2 |

| UK | 5 | 4 |

| USA | 4 | 6 |

Table A2.11: Wealth per adult

| Country | GDP per adult (USD)-2021 | Wealth per adult 2000 USD) | Wealth per adult (USD) 2022 | Total wealth 2022 USD Billion | Share in global wealth 2022 |

| China | 15,624 | 4,247 | 75,731 | 84,485 | 18.6 |

| India | 3,561 | 2,643 | 16,500 | 15,365 | 3.4 |

| USA | 100,380 | 215,146 | 551,347 | 139,866 | 30.8 |

Table A2.12 : Distribution of wealth

| Share in the county’s wealth (%) | |||||

| Bottom | Top | ||||

| Country / Year | 80% | 90% | 10% | 5% | 1% |

| China | |||||

| 2002 | 45.4 | 62.9 | 37.1 | NA | NA |

| 2013 | 34.5 | 51.6 | 48.4 | NA | NA |

| India | |||||

| 2002 | 30.1 | 47.1 | 52.9 | 38.3 | 15.7 |

| 2018 | NA | 47.6 | 52.4 | NA | 18.3 |

| United States | |||||

| 2001 | 22.1 | 39.2 | 60.8 | 49.3 | 25.4 |

| 2020 | 15.7 | 30.3 | 69.7 | 57.8 | 31.4 |

| 2023 | 17.8 | 32.0 | 68.0 | 57.0 | 30.6 |

distribution data: Page 15

Table A2.13: Share of Financial Wealth in Total wealth of selected countries (in %)

| Year | World | China | India | USA |

| 2000 | 55.4 | 36.4 | 24.1 | 68.1 |

| 2005 | 51.3 | 37.4 | 24.1 | 63.0 |

| 2010 | 50.6 | 40.9 | 24.2 | 70.1 |

| 2015 | 53.1 | 43.4 | 21.6 | 72.2 |

| 2020 | 53.9 | 44.2 | 23.9 | 73.1 |

| 2021 | 53.6 | 44.7 | 21.8 | 72.2 |

| 2022 | 51.1 | 45.4 | 21.0 | 67.6 |

Table: A2.14: Share of selected regions and countries in the world’s total adult population and household wealth.

| 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2022 | |||||

| Region/ Country | Adult Population | Wealth | Adult Population | Wealth | Adult Population | Wealth | Adult Population | Wealth |

| Africa | 10.1 | 0.6 | 11.2 | 1.1 | 12.8 | 1.3 | 13.2 | 1.3 |

| Asia-Pacific | 22.3 | 24.2 | 23 | 22.4 | 23.7 | 18.1 | 23.8 | 17.2 |

| Europe | 14.6 | 29.3 | 12.9 | 31.8 | 11.3 | 25 | 11 | 23 |

| Latin America | 8.1 | 2.3 | 8.3 | 3.5 | 8.6 | 2.7 | 8.6 | 3.3 |

| North- America | 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| China | 23.2 | 3.1 | 22.6 | 10.1 | 21.1 | 17.5 | 20.8 | 18.6 |

| India | 15.7 | 1.3 | 16.4 | 2.7 | 17.2 | 3 | 17.4 | 3.4 |

| USA | 5.4 | 36.9 | 5 | 25.7 | 4.8 | 29.9 | 4.7 | 30.8 |

Table A2.15: Wealth of Billionaires in China, India and USA

| 2010 | 2020 | 2022 | 2022 | ||||

| Country | No | Wealth | No | Wealth | No | Wealth | % of wealth of the country |

| China | 64 | 133.2 | 387 | 1177.5 | 539 | 1962.5 | 2.3% |

| India | 49 | 222.1 | 102 | 312.6 | 166 | 749.8 | 4.9% |

| USA | 403 | 1349.3 | 615 | 2948.7 | 735 | 4701.1 | 3.4% |

Table A2.17: Number of Millionaires (in thousands)

| Country | 2020 | 2022 | Percentage of the World-2020 | Percentage of the World-2022 |

| United States | 7,642 | 22,710 | 52.0% | 38.2% |

| Mainland China | 39 | 6,231 | 0.3% | 10.5% |

| France | 404 | 2,821 | 2.7% | 4.7% |

| Japan | 2,472 | 2,757 | 16.8% | 4.6% |

| Germany | 622 | 2,627 | 4.2% | 4.4% |

| United Kingdom | 716 | 2,556 | 4.9% | 4.3% |

| Canada | 269 | 2,032 | 1.8% | 3.4% |

| Australia | 113 | 1,840 | 0.8% | 3.1% |

| Italy | 427 | 1,335 | 2.9% | 2.2% |

| Korea | 90 | 1,254 | 0.6% | 2.1% |

| Netherlands | 257 | 1,175 | 1.7% | 2.0% |

| Spain | 172 | 1,135 | 1.2% | 1.9% |

| Switzerland | 195 | 1,099 | 1.3% | 1.9% |

| India | 37 | 849 | 0.3% | 1.4% |

| Taiwan | 110 | 765 | 0.7% | 1.3% |

| Hong SAR | 118 | 630 | 0.8% | 1.1% |

| Belgium | 107 | 536 | 0.7% | 0.9% |

| Sweden | 54 | 467 | 0.4% | 0.8% |

| Brazil | 33 | 413 | 0.2% | 0.7% |

| Russia | 17 | 408 | 0.1% | 0.7% |

| World | 14,695 | 59,391 |

Annexure 3

Inequality in terms of ownership of assets, and future income from this wealth is not exclusive to market economies. Nor was it a universal characteristic across all previous societies of Homo sapiens. It has been agued by many archeologists that hierarchy of status and dominance of few over many began with agricultural revolution in the last phase of Neolithic society, also known as Neolithic revolution.

A research paper published in Nature in the year 2017 compared and quantified the degree of inequality in 63 Neolithic society using Gini coefficient. For computing this coefficient, the distribution of household size was considered as a proxy for wealth. The referenced period of the study, called Old World, ranged from 11000 to 2000 years ago. The study also covered a period termed New World, which ranged from around 3,000 to about 300 years ago. The study shows that as compared to hunter-gatherers, wealth inequality generally increased when human beings started domestication of plants and animals. Ownership of large land areas became economically valuable only with the ability to harness plough animals like oxen (Kohler Timothy (2017).

In 2019, another study using data from 39 Neolithic-Iron Age sites, found that farming per se did not result in enduring and significant wealth inequality in ancient agricultural societies. Such a phenomenon emerged only in societies where land was a relatively scarce asset as compared to labour-scarce societies (Bogaard Amy et al. 2019)

References

Bogaard Amy, Mattia Fochesato, and Samuel Bowles, 2019 The farming-inequality nexus: new insights from ancient Western Eurasia Antiquity / Volume 93 / Issue 371 / October 2019: Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 September 2019, pp. 1129-1143

Chen S and Zhang D(2021). Impact of air pollution on labor productivity: Evidence from prison factory data, China Economic Quarterly International 1 148–159 ; see also https://www.unep.org/interactives/air-pollution-note/

Credit Suisse Research Institute (CSRI) (2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020 and others) Global Wealth Report 2022 Leading perspectives to navigate the future; UBS / CSRI (2023, 2022,2021) . Global Wealth Databook 2023, 2022,2021

Davies James B (2008). An Overview of Personal Wealth pp 1-26 in James B. Davies (ed) Personal Wealth: From a Global Perspective, Oxford , New York

- Estelle Dominati, Murray Patterson , and Alec Mackay, A framework for classifying and quantifying the natural capital and ecosystem services of soils, July 2010, Ecological Economics 69(9):1858-1868 available online also

Fisher, Irving(1906): The nature of capital and Income, Macmillan, New York

Kohler Timothy A(2017) Greater post-Neolithic wealth disparities in Eurasia than in North America and Mesoamerica, Nature, Published online 15 November 2017.

Kaggle. Comprehensive Data on Billionaires from 1997-2024; Accessed on October 20 2024 https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/guillemservera/forbes-billionaires-1997-2023

UBS 2023- Billionaire Ambitions report. https://www.ubs.com/global/en/wealthmanagement/family-office-uhnw/reports/billionaire-ambitions-report-2023.html

United Nations and World Bank, System of National Accounts 1993. Brussels/Luxembourg, Washington, D.C., Paris, New York, 1993.

United Nations 2003. Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/environment/seea2003.pdf

United Nations 2008, System of National Accounts2008https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/sna2008.pdf

World Bank. 1997. Expanding the Measure of Wealth: Indicators of Environmentally Sutainable Development. Environmentally Sustainable Development Studies and Monographs Series No. 17. Washington, DC: World Bank

World Bank (2006), Where Is the Wealth of Nations? Measuring Capital for the 21st Century. Washington DC World Bank

World Bank 2011. The Changing Wealth of Nations, Measuring Sustainable Development in the New Millennium , Washington DC

World Bank. Database https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/world-development-indicators/series/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD?fbclid=IwAR3VlnTX31huRXCibX_YcTsylgjPg3YHqi6O0N0hXrW8isbchSFlLEUDzZo World Bank. 2021. The Changing Wealth of Nations 2021: Managing Assets for the Future. Washington, DC: World Bank. See also https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/wealth-accounting